“What … is type? It can most simply be defined as a concept which describes a group of objects characterized by the same formal structure. It is neither a spatial diagram nor the average of a serial list. It is fundamentally based on the possibility of grouping objects by certain inherent structural similarities”

From Rafael Moneo’s 1978 essay “On Typology”, published in Oppositions magazine.

• Early Occurrences of Typology

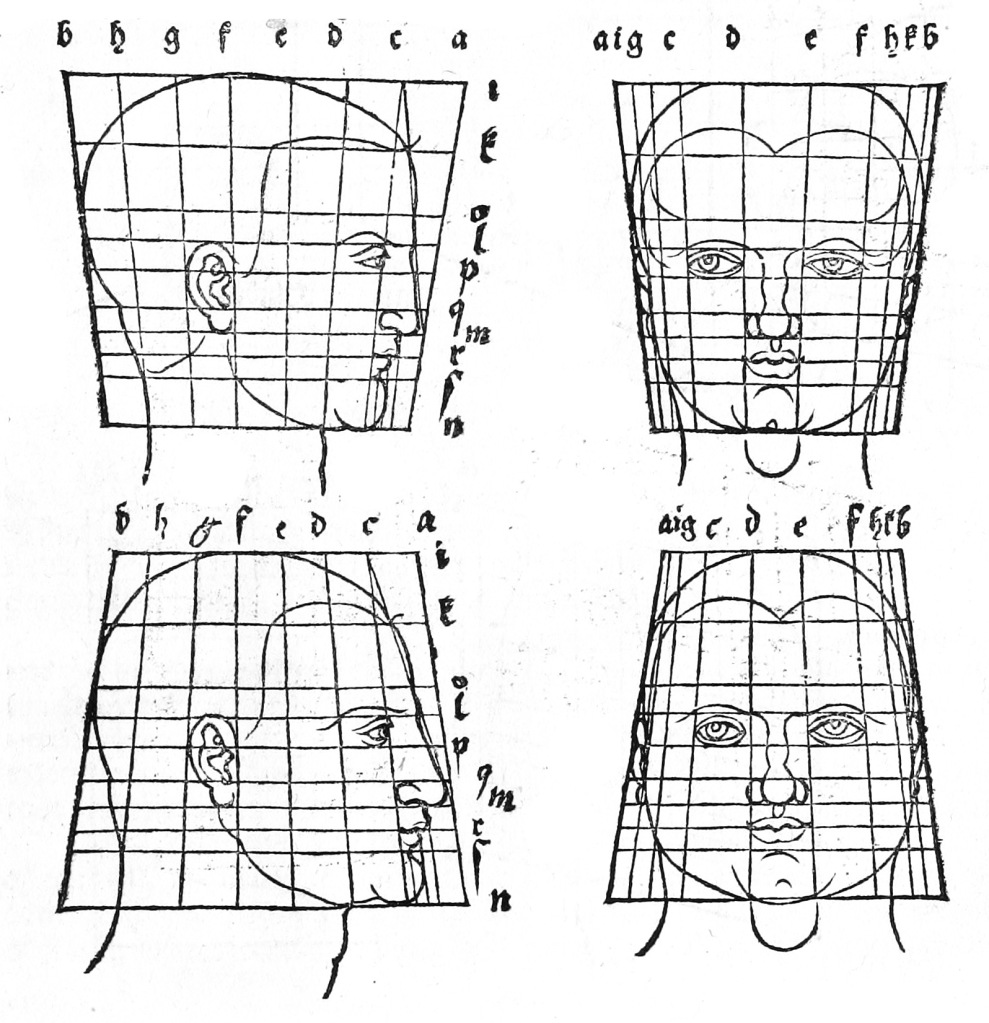

Where does categorizing, or typing, begin? From 1532-1534 Albrecht Dürer’s publishes the Four Books on Human Proportion (Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion). In the third book, Dürer gives principles by which the proportions of the figures can be modified, including the mathematical simulation of convex and concave mirrors.

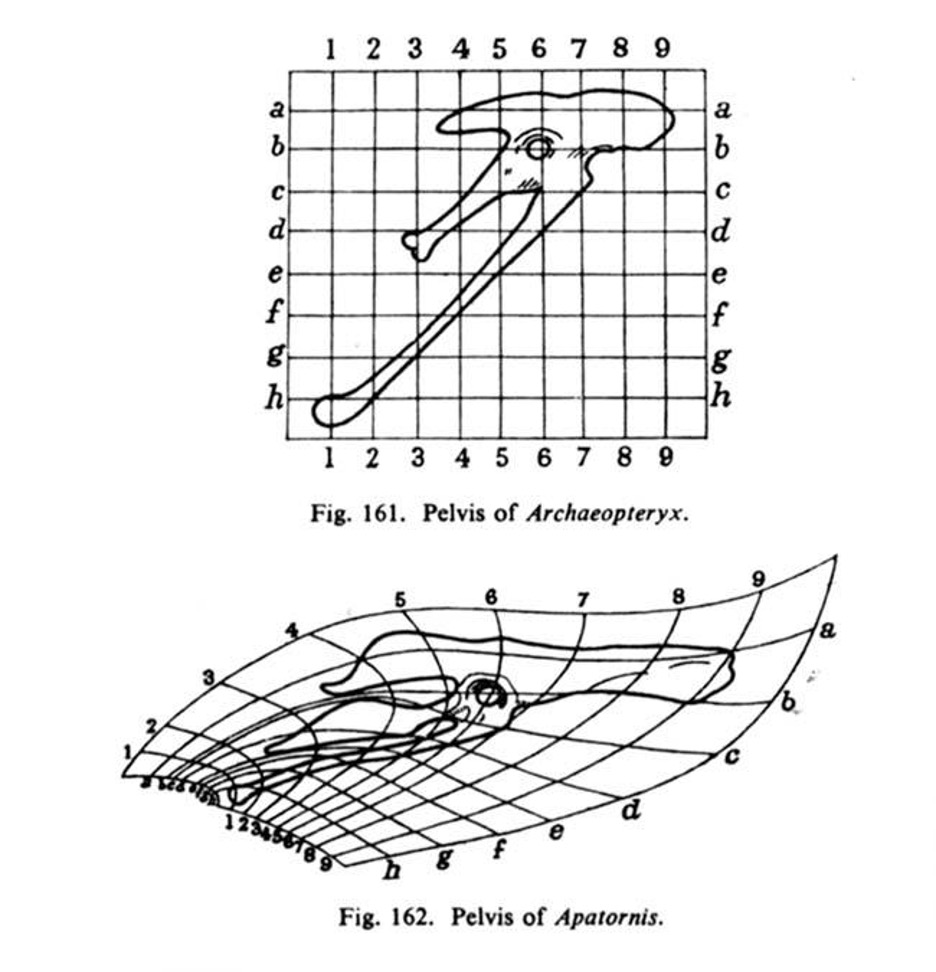

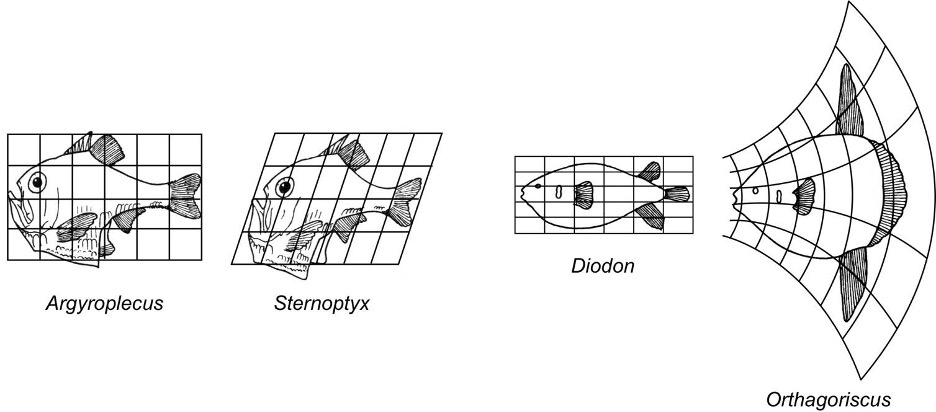

In 1917 D’Arcy Thompson publishes On Growth and Form. In this book Thompson, having studied Dürer’s illustrations, develops a similar geometric transformation to illustrate how the forms of organisms and their parts, whether leaves, the bones of the foot, human faces or the body shapes of copepods, crabs or fish, can be explained.

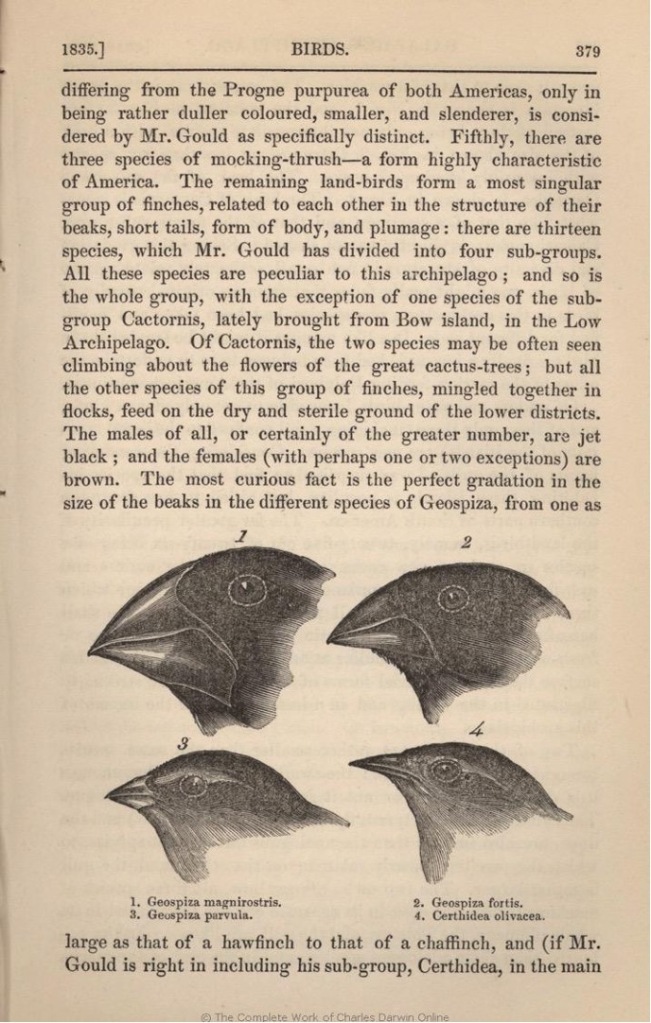

Prior to Thompson’s work, in Charles Darwin’s treatise of 1859, On the Origin of Species, he categorizes 12 species of Galápagos finches. This is done by studying their typical makeup. He notes the similarities, and differences, that occurred due to their habitat, i.e. the beaks.

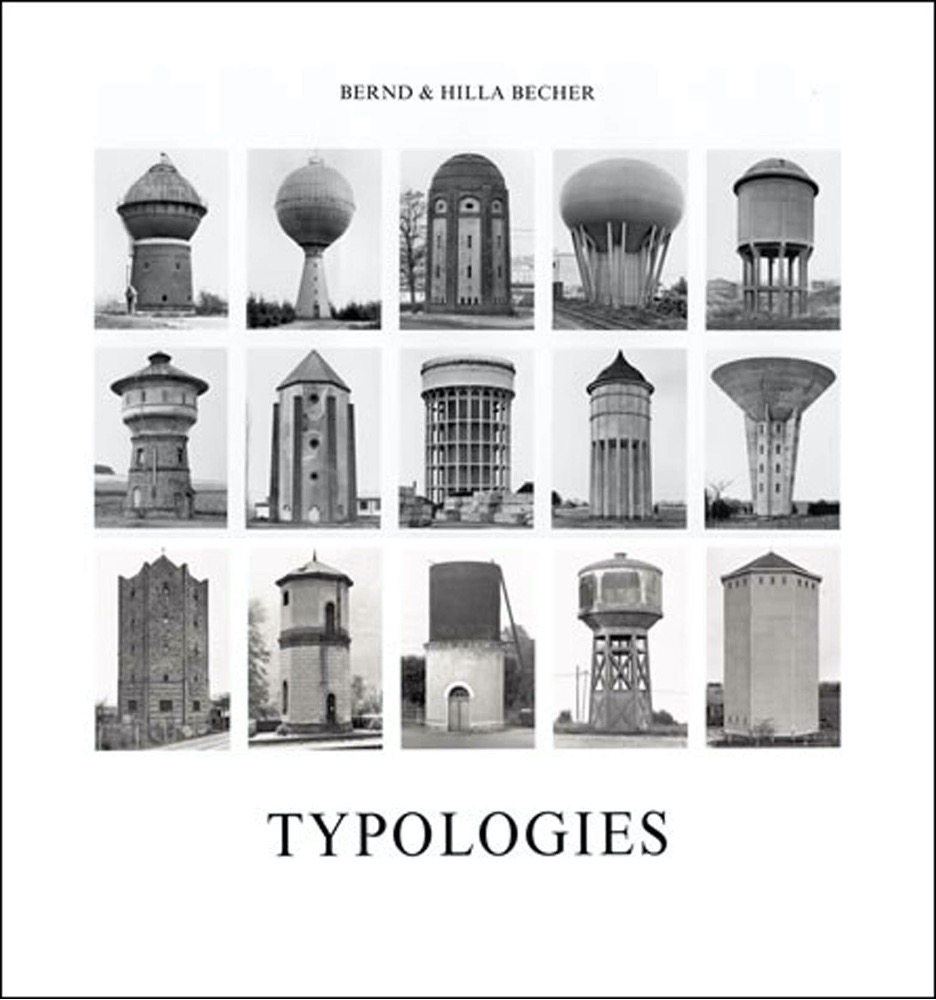

• Typology in the Art of Photography

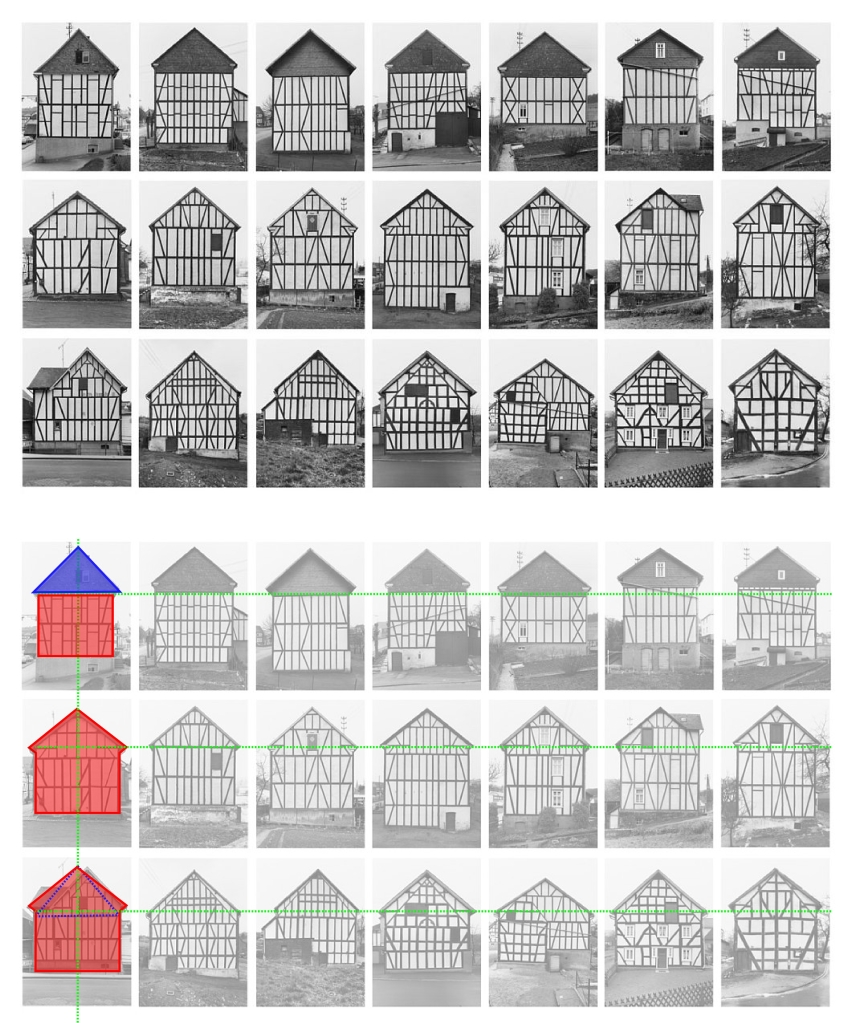

This concept of typing can occur in just about any field. Below are two examples of typing in photography. The first, by Brend & Hilla Becher, were German conceptual artists and photographers working as a collaborative duo. They are best known for their extensive series of photographic images, or typologies, of industrial buildings and structures, often organized in grids.

In this second example I am the author. I composed a series of flowers similar to the Becher’s process, and arranged them by, orientation, shape, and color, and in a grid As with the Becher’s work, the images can be viewed individually, but are combined to make one image as a final piece.

• Typology in Architecture and Urban Design

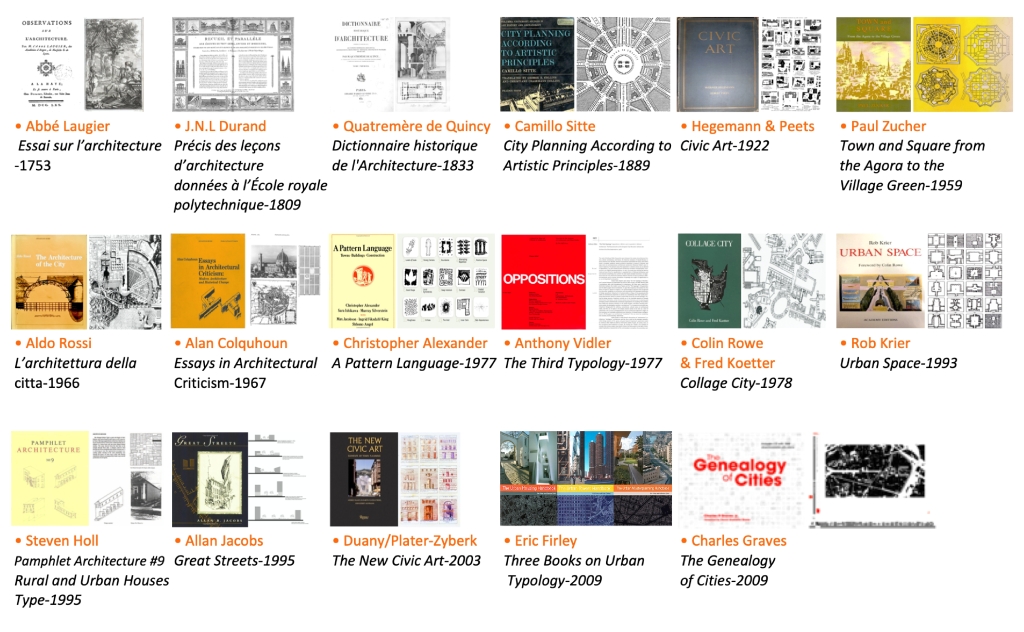

Within architecture and urban design typology is the comparative study of physical or other characteristics of the built environment into distinct types. It’s important to understand the historic writings on typology in the field of architecture and urban design. I’ll briefly list some of these writings in chronological order.

Historically the use of typology for the study and design of architecture began during the age of enlightenment and can be traced to Abbé Laugier (1713-96) as described in his Essai sur l’architecture, 1753.

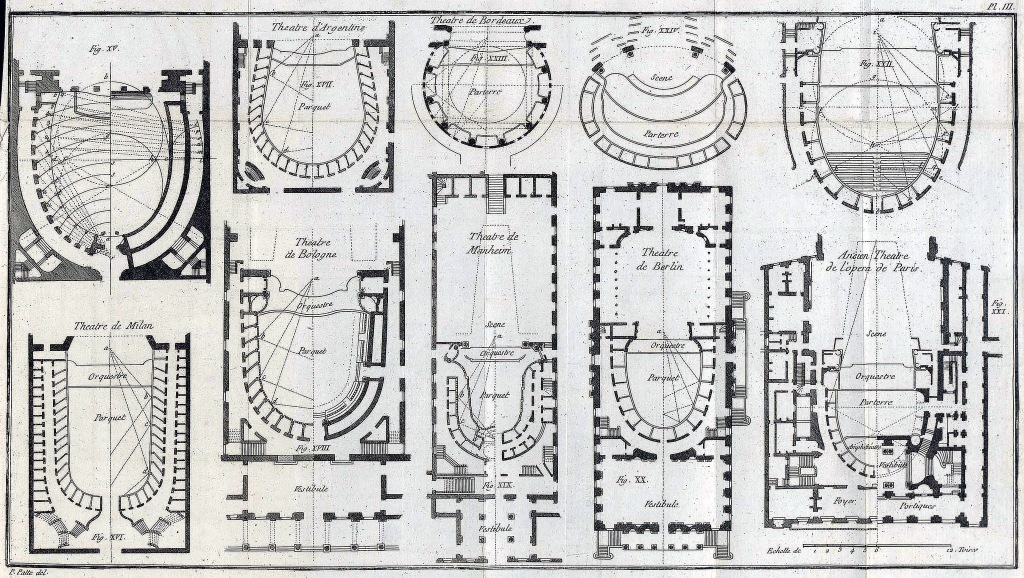

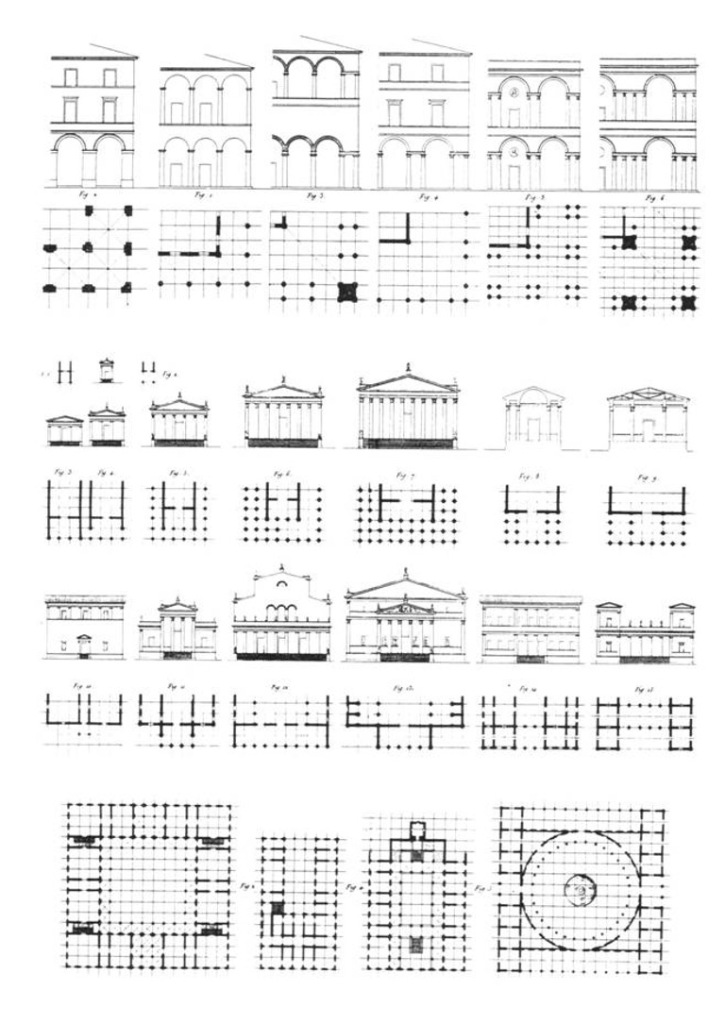

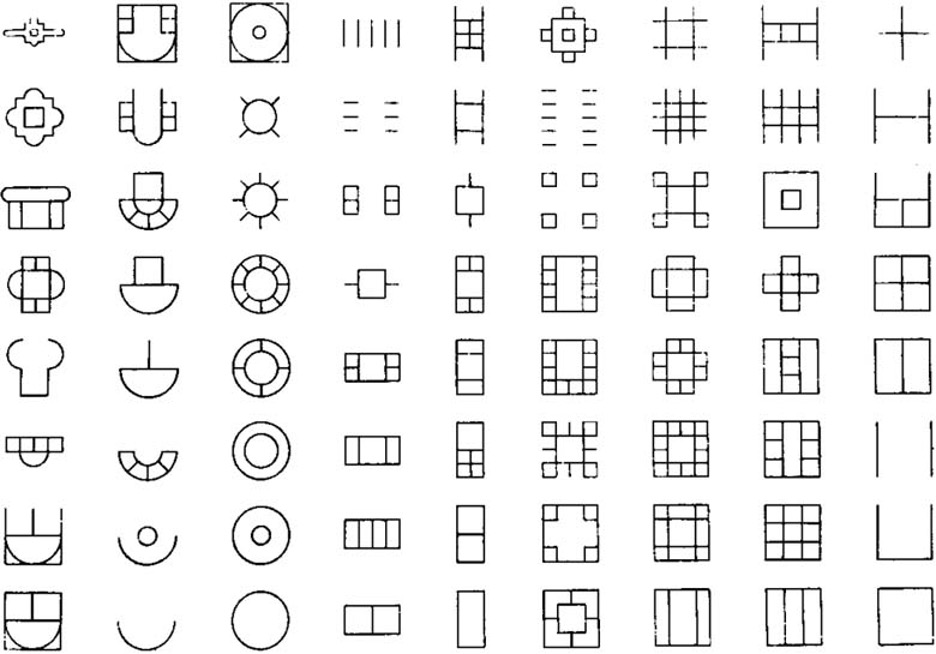

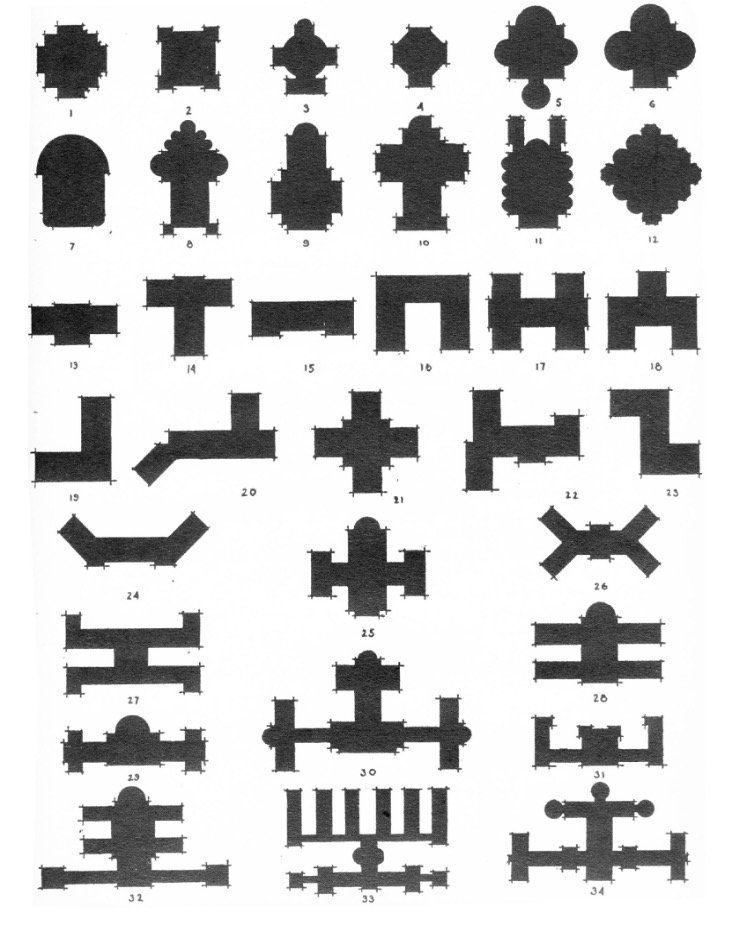

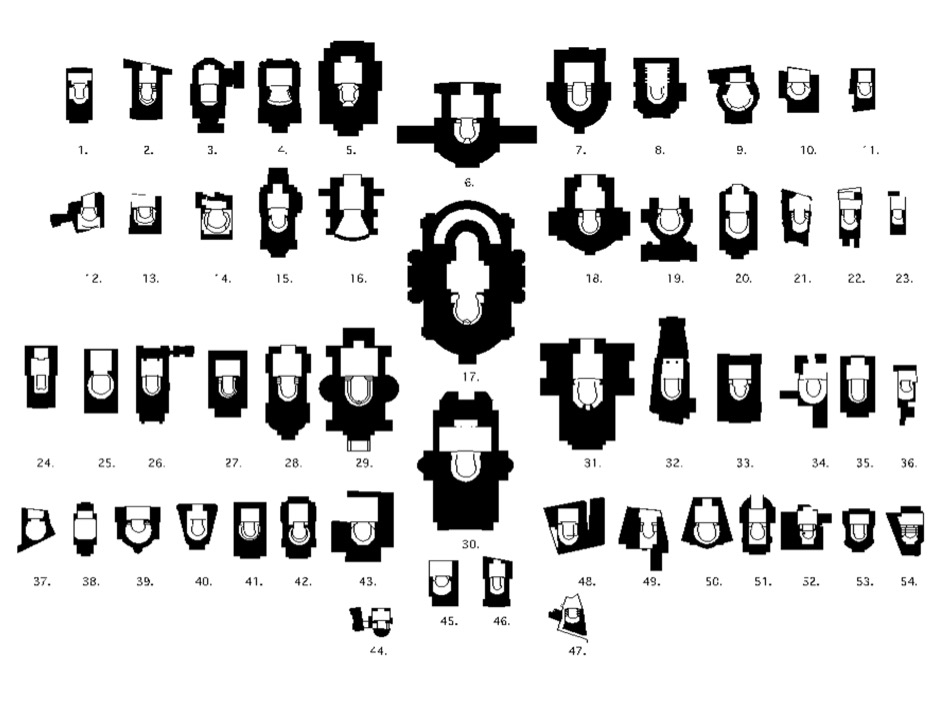

Following Abbé Laugier’s essay on architecture was the work of architectural typing by J.N.L Durand, Précis des leçons d’architecture données à l’École royale polytechnique published in 1809. Durand taught at the École Polytechnique and developed a system to illustrate typical building components, and designs. Later he also created a series of small parti pris diagrams describing common formal plan types in architecture.

This next example is by Quatremère de Quincy. In 1832-33 he published Dictionnaire historique de l’Architecture, .

Continuing in chronological order, below is an example from John Theodore Haneman’s, A Manual of Architectural Compositions, 1923.

In 1962 Giulio Carlo Argan’s essay On the Typology of Architecture revived the idea of type. Aldo Rossi’s 1966 Varchitettura della citta (The Architecture of the City) strengthened its importance, and reintroduces the idea of typology and the design of urbanism.

• Typology and Urban Design

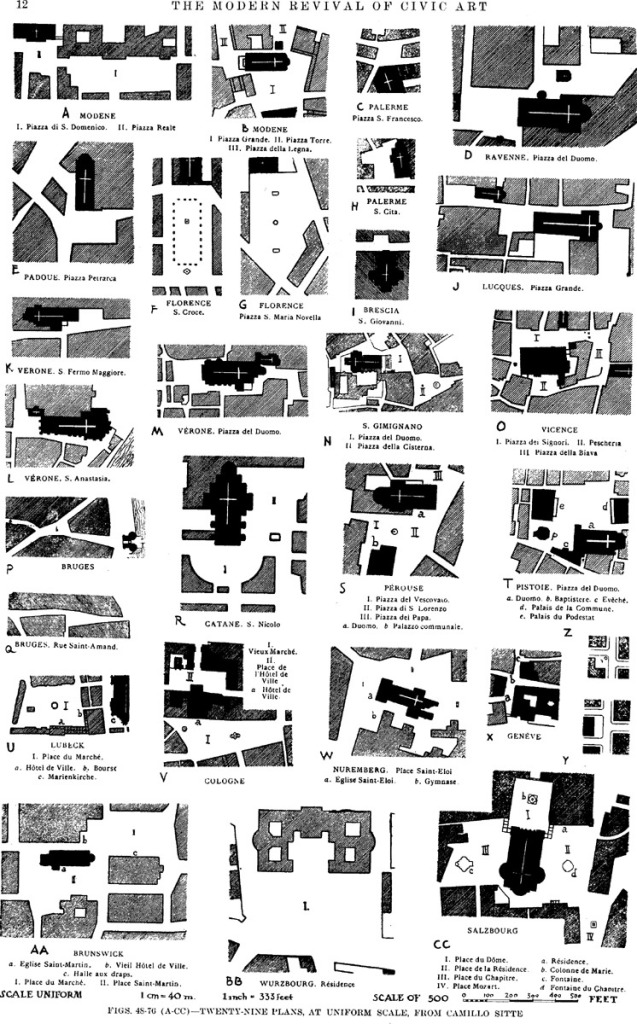

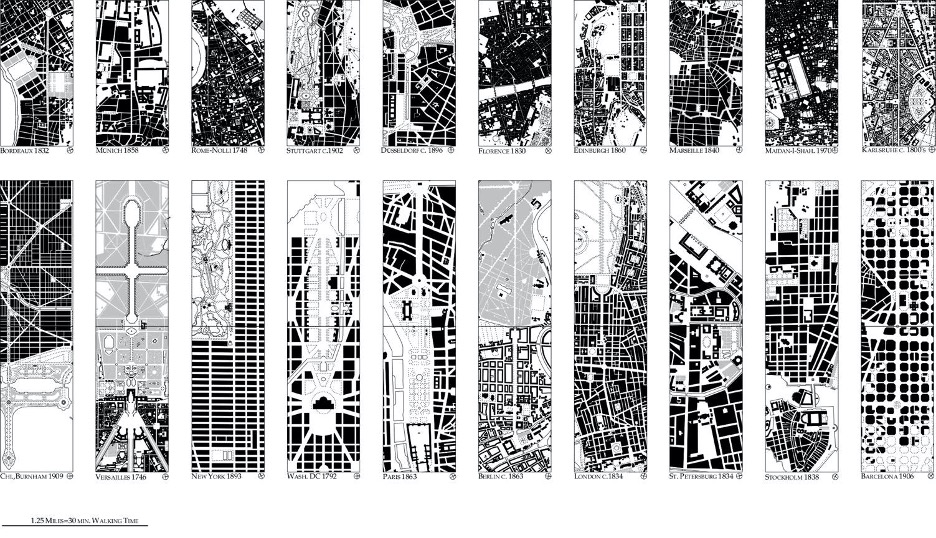

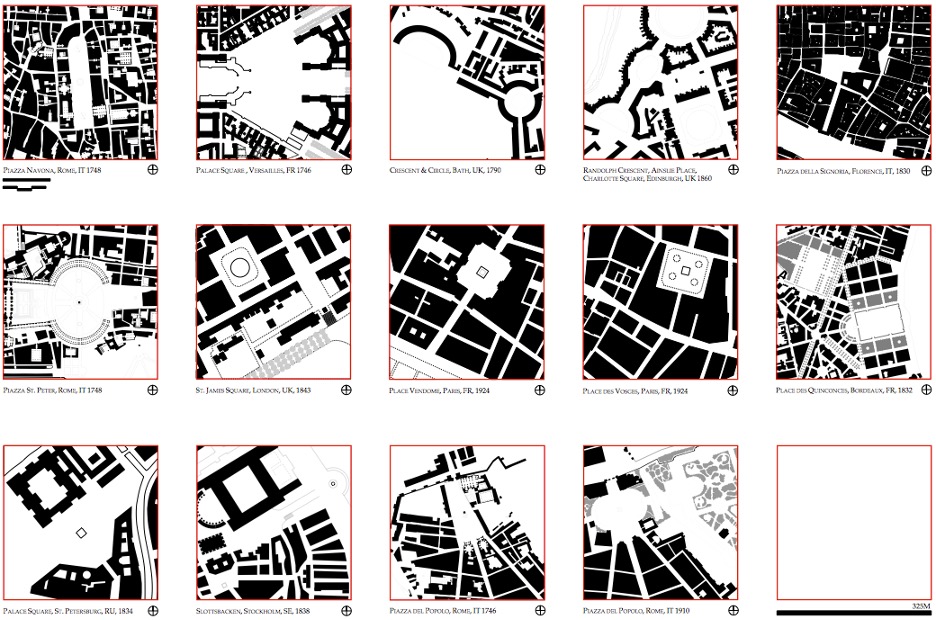

The actual early investigation of typology and urbanism occurs with the work of Camillo Sitte, an Austrian architect. Sitte publishes City Planning According to Artistic Principles in 1889. In his book he studies important city squares (piazze, platz, or place, etc.) He draws the squares in a similar format, and at the same scale, allowing for quick comparison.

• The Process of Developing Typologies

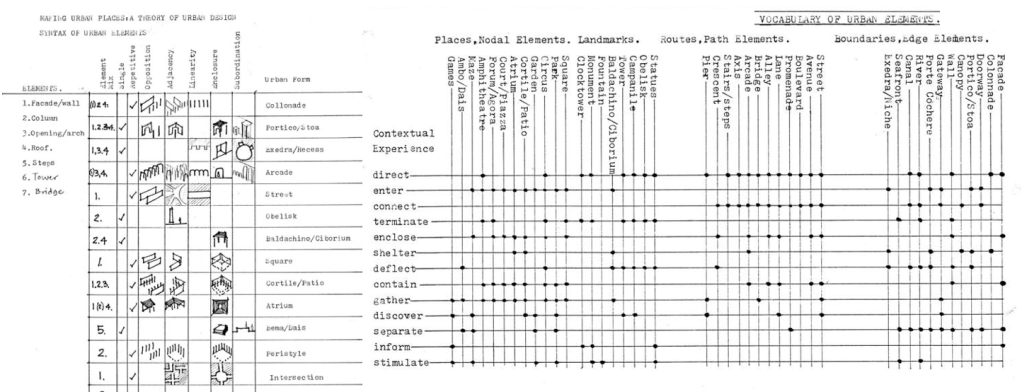

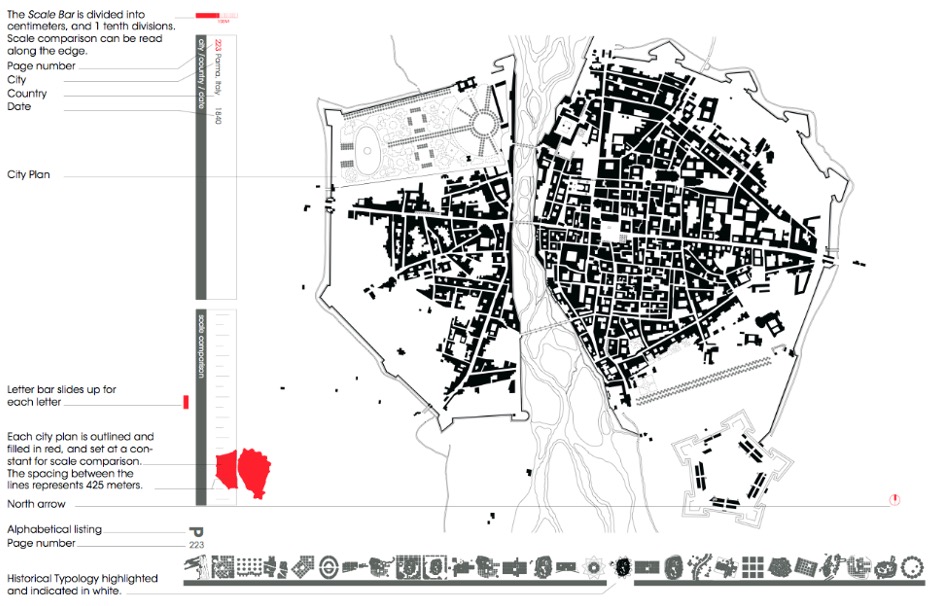

While working on The Genealogy of Cities I began to determine which parts of the urban fabric should be investigated. The graph below was an early first attempt of identifying possible urban typologies that could be compared and contrasted.

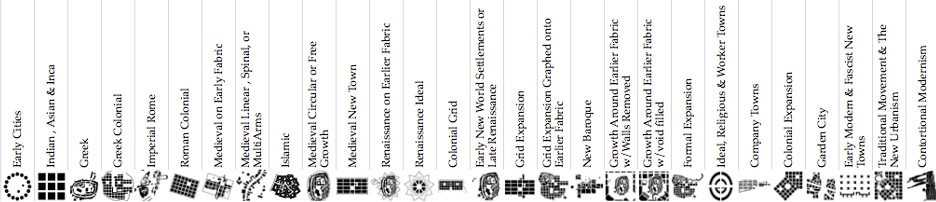

In the end, as shown below, I generated a series of icons that represented identifiable historic stages in the design of urban fabric.

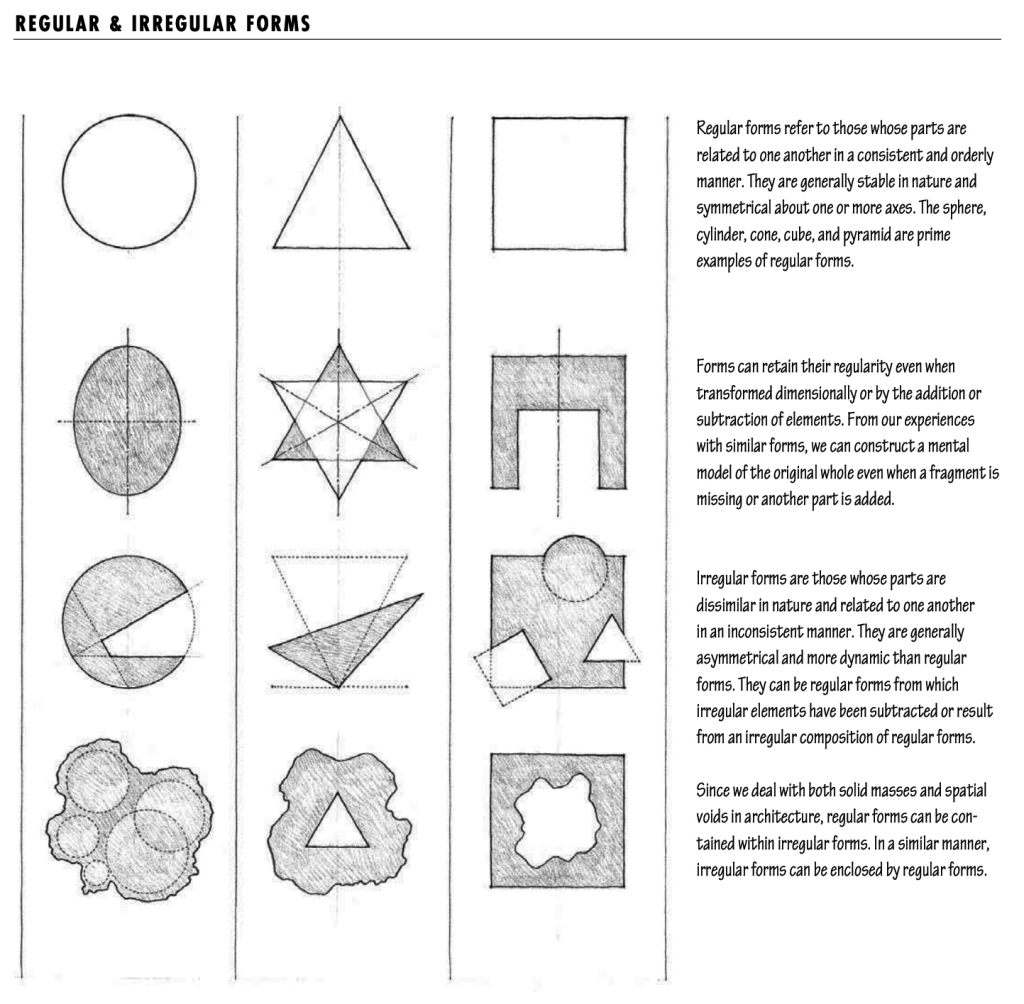

One of the clearest uses of typology as an instructional tool is Francis D. K. Ching’s text Architecture: Form Space and Order.

• Practical Uses of Typology for Design

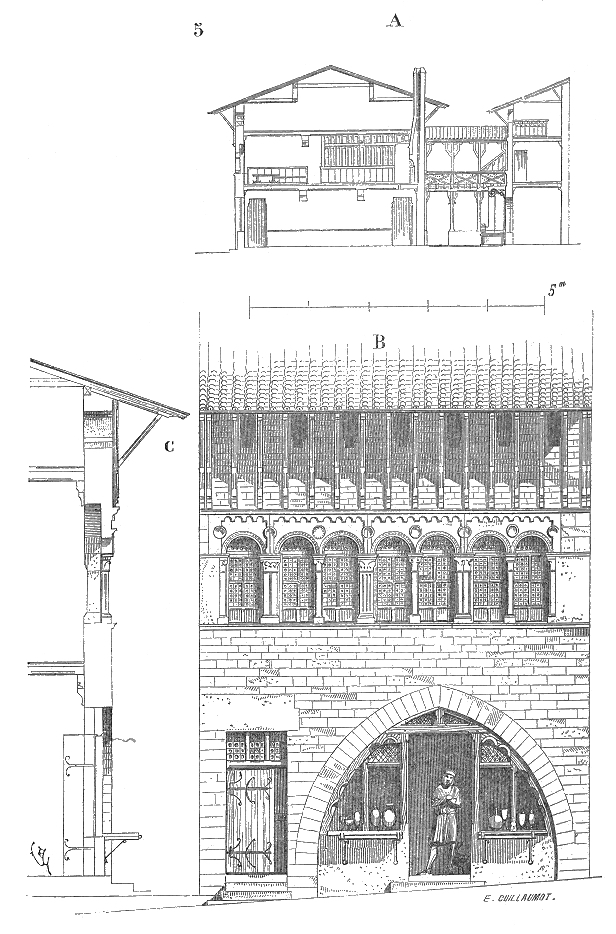

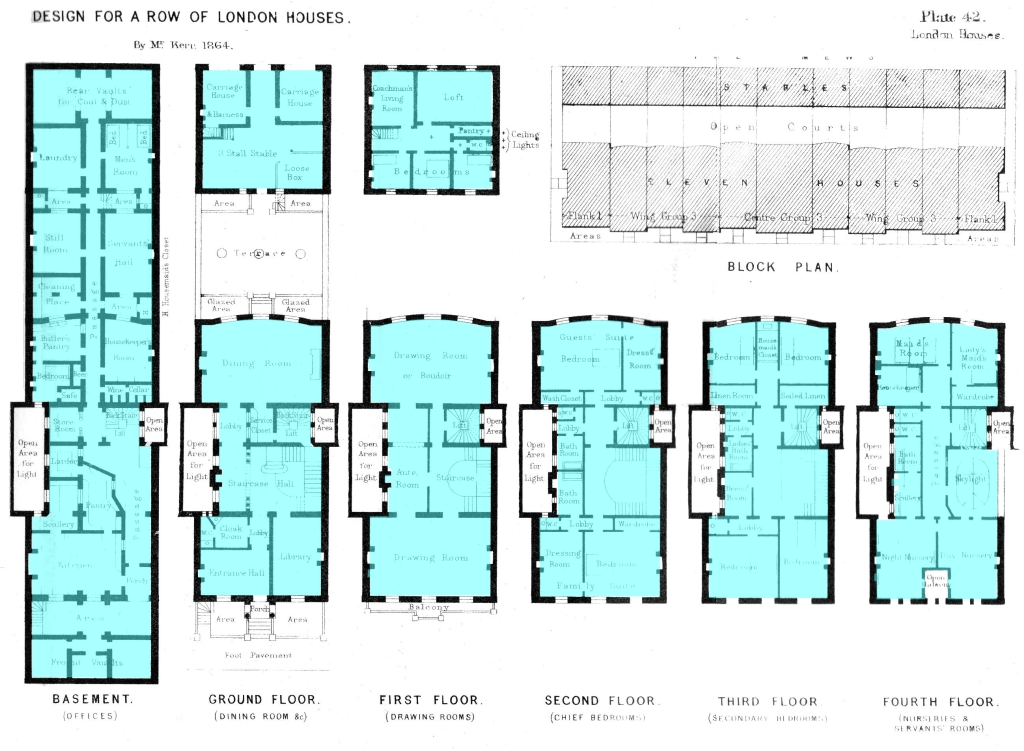

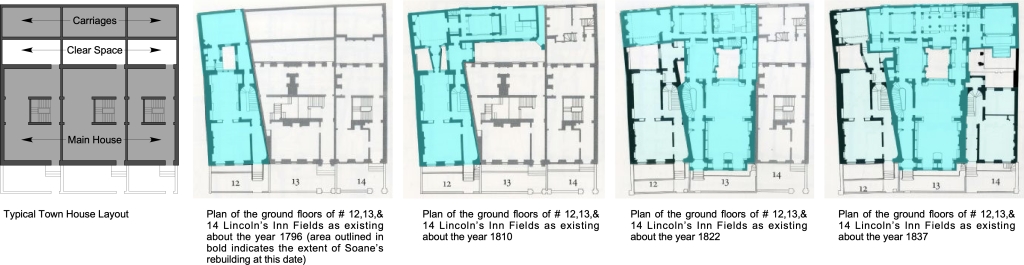

I’ve had many a discussion with colleagues and students who have asked, “Does the use of typological studies really aid in design of architecture and urban design?” Personally, I believe if you know the process of developing typologies, then you are able to deviate from the norm at any time. I’ll illustrate this by looking at the example of Sir John Soane’s design for his row house in London, at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. First though, a typical London row house.

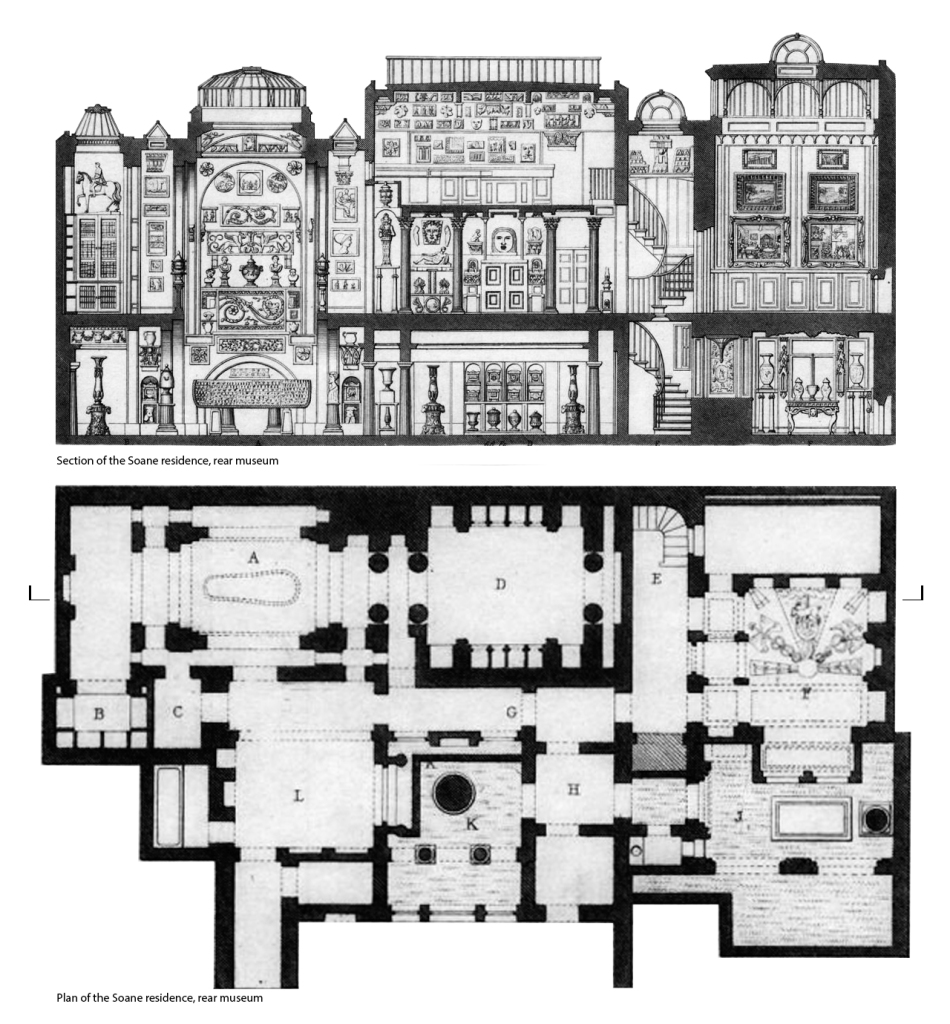

In Soane’s case, “…Soane demolished and rebuilt three [typical Georgian row] houses in succession on the north side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He began with No. 12 (between 1792 and 1794), externally a plain brick house. After becoming Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy in 1806, Soane purchased No. 13, the house next door, today the museum, and rebuilt it in two phases in 1808–09 and 1812.

In 1808–09 Soane constructed his drawing office and “museum” on the site of the former stable block at the back, using primarily top lighting. In 1812 he rebuilt the front part of the site, adding a projecting Portland Stone façade to the basement, ground and first floor levels and the [center] bay of the second floor. Originally this formed three open loggias, but Soane glazed the arches during his lifetime. Once he had moved into No. 13, Soane rented out his former home at No. 12…

After completing No.13, Soane set about treating the building as an architectural laboratory, continually remodeling the interiors. In 1823, when he was over 70, he purchased a third house, No. 14, which he rebuilt in 1823–24. This project allowed him to construct a picture gallery, linked to No.13, on the former stable block of No. 14. The front main part of this third house was treated as a separate dwelling and let as an investment; it was not internally connected to the other buildings. When he died No. 14 was bequeathed to his family and passed out of the museum’s ownership.”

Wikipedia entry, Sir John Soane’s Museum.

• Examples of Typology Studies by Former Students

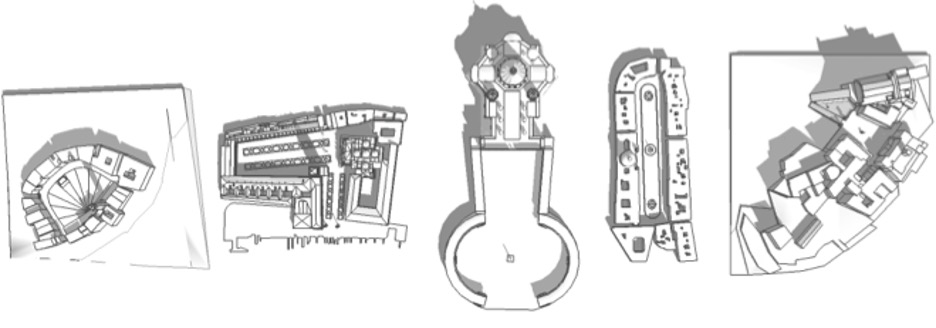

The following are some examples of both architectural and urban typology studies created by some of my former students. These studies were early exercises and were tools for understanding both architectural programing and urban space.

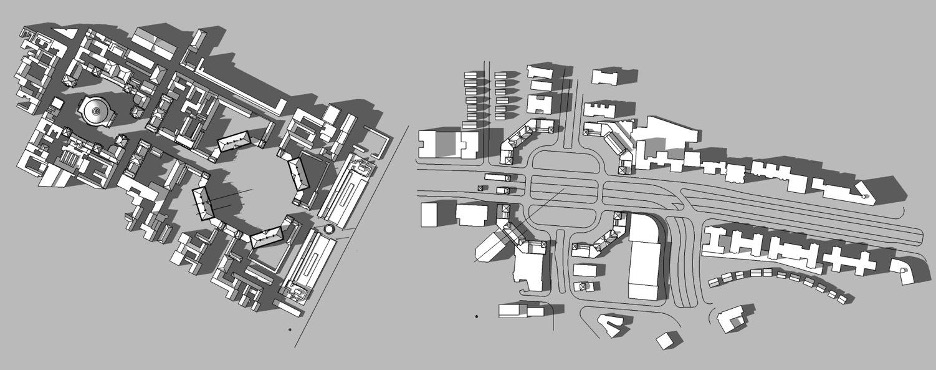

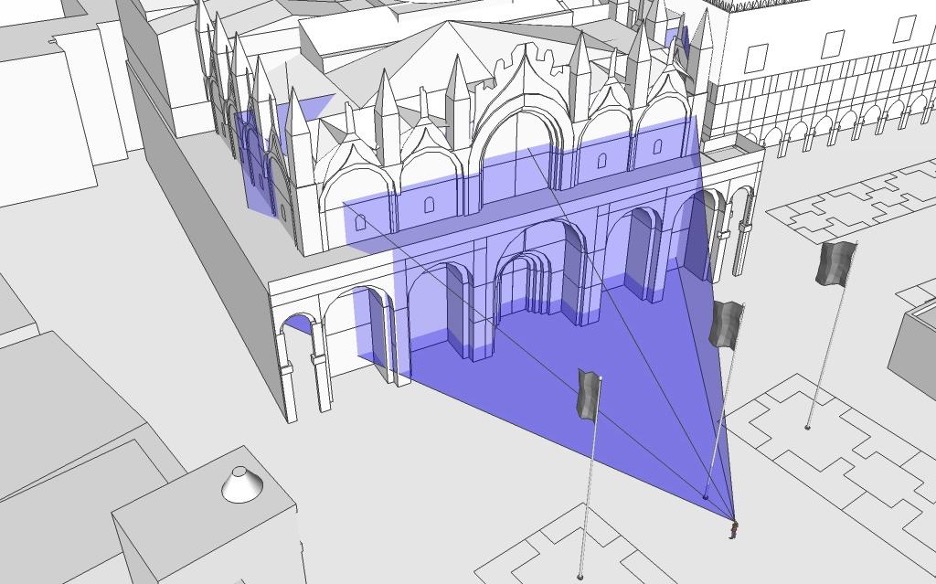

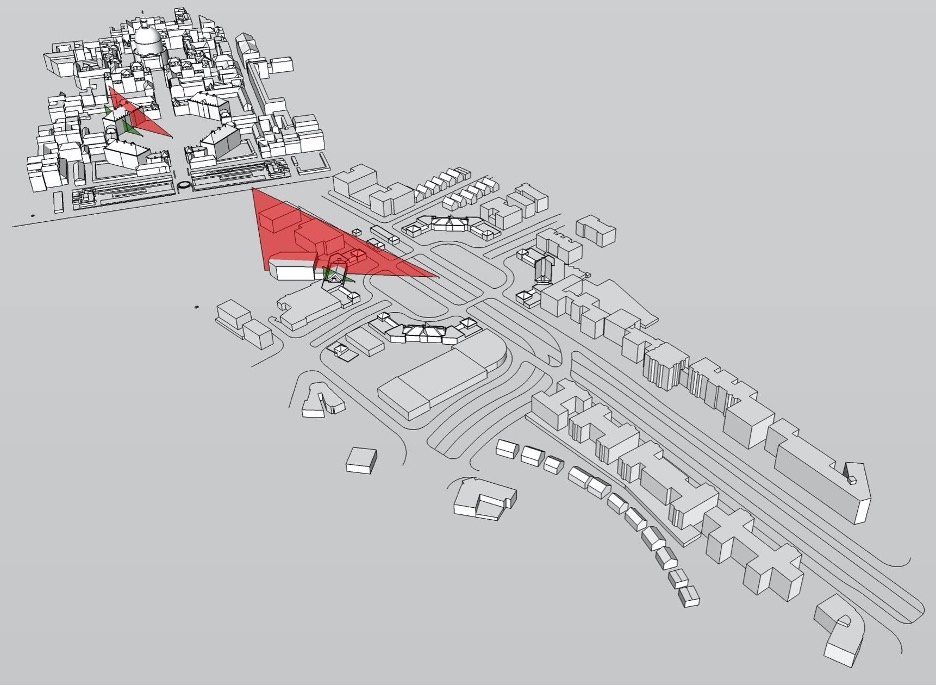

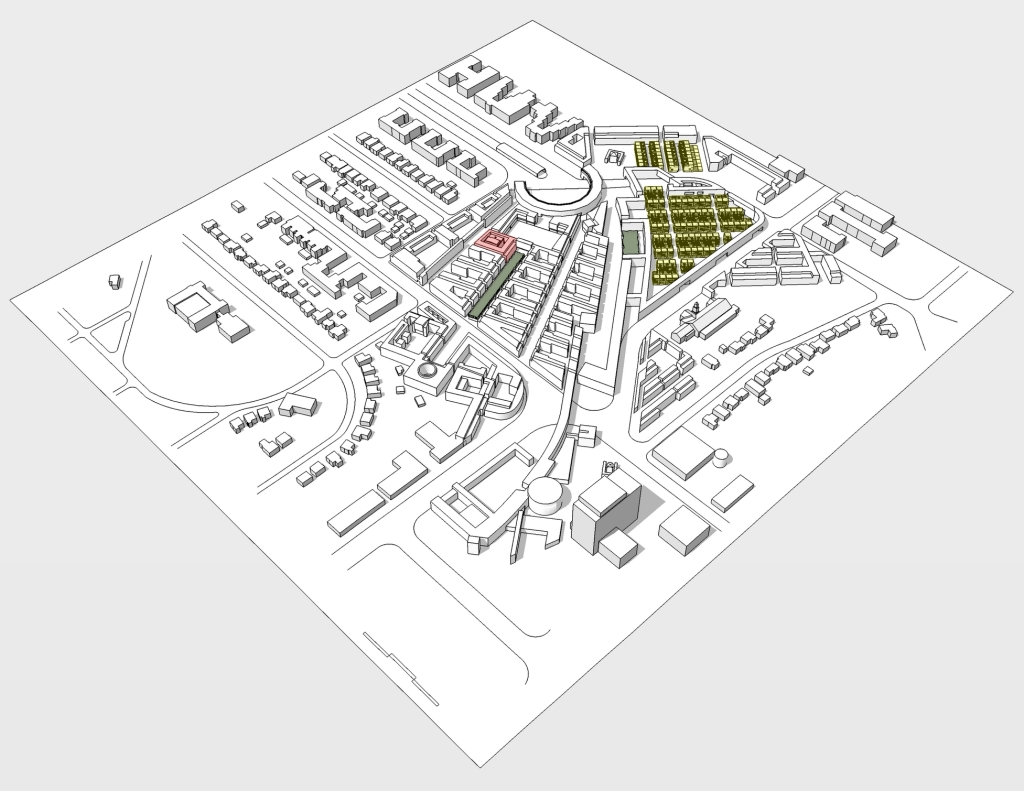

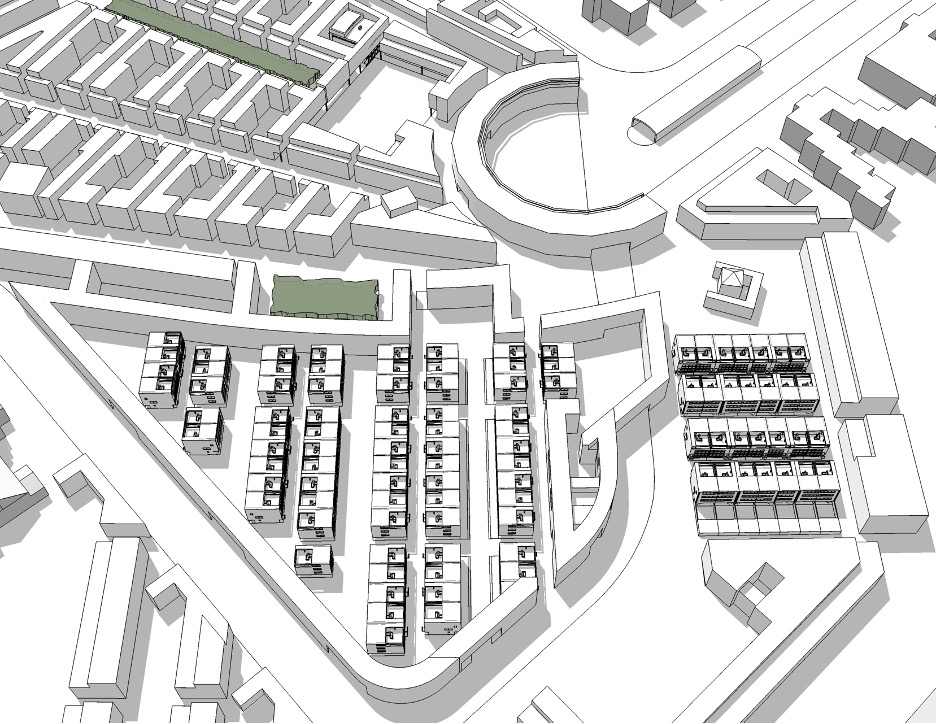

These next three examples are investigations of comparable urban conditions.

• Using Typological Studies for Designing

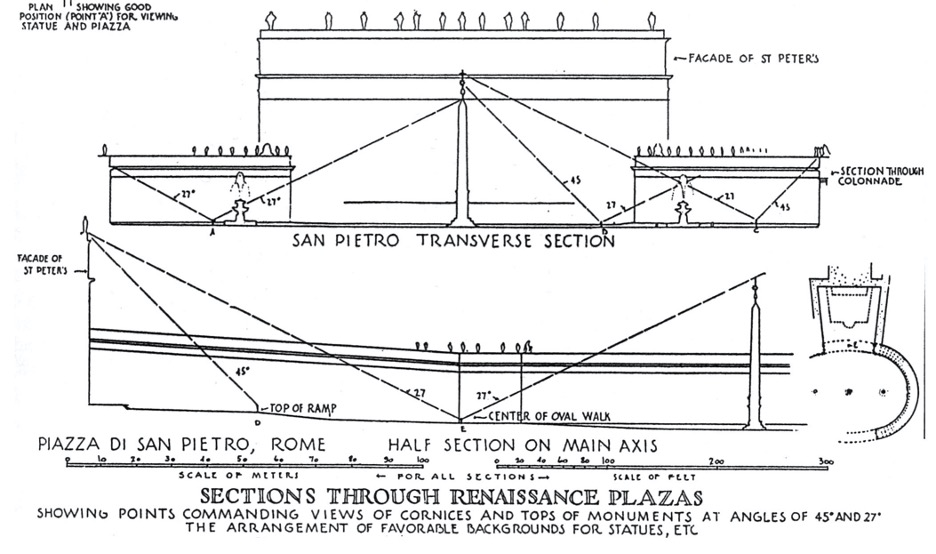

The above illustration is displayed in Hegemann and Peets, The American Vitruvius: An Architects’ Handbook of Civic Art. The section through Piazza di San Pietro illustrates ‘good positions for viewing’ within the space. The angles of 27 and 45 degrees are the typical human viewing angles for a person looking straight ahead, and when tilting your head up.

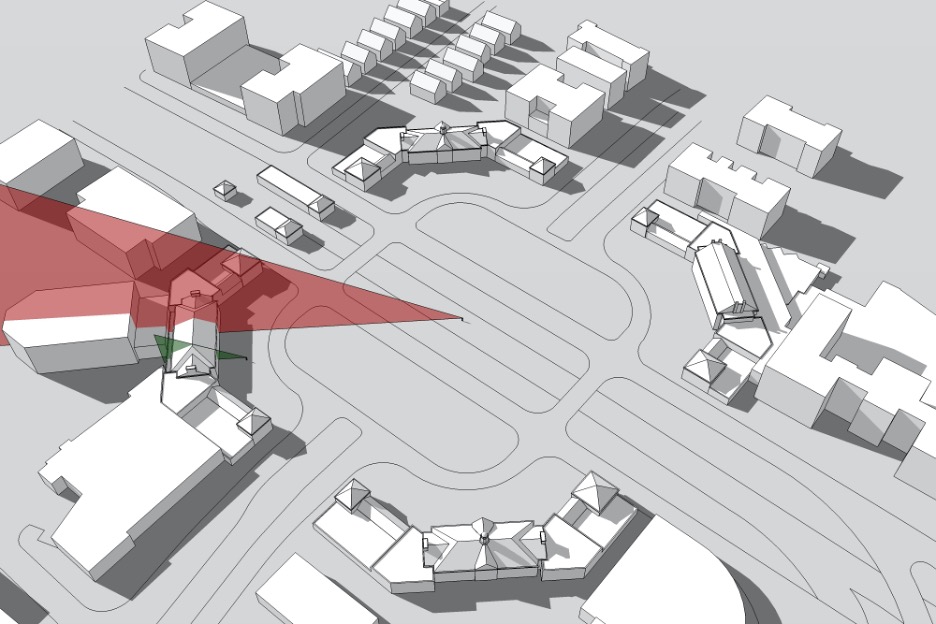

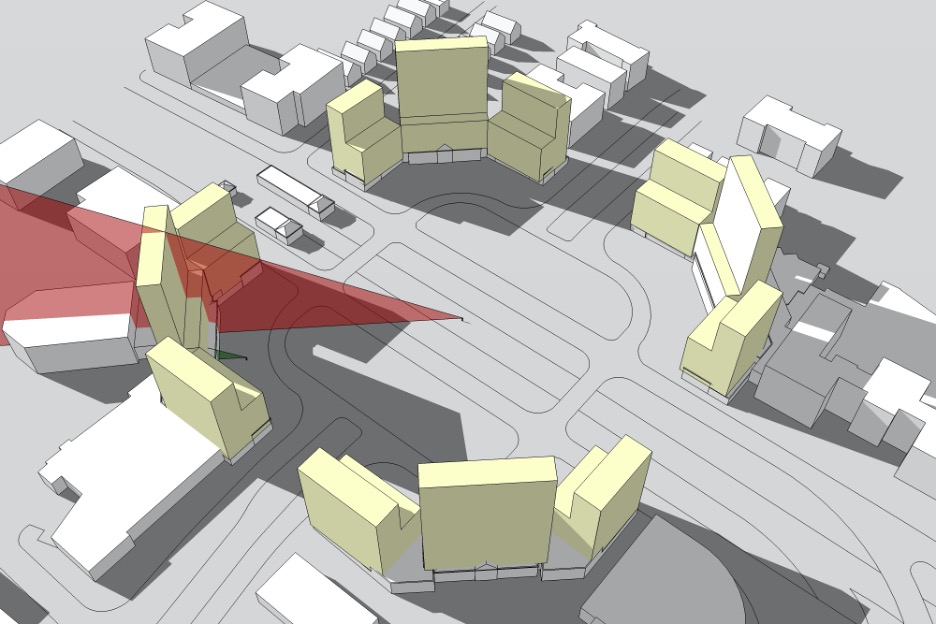

The earlier discussion and examples of typology of row housing and theaters were used within a third-year design studio that focuses on the introduction to urban design. To fully understand the semester long exercise I refer you to my personal website, where I go into depth describing the exercises. The following is an example of one student’s solution.

This is just a brief introduction of typology in architecture and urban design. Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions, or want to add to the discussion.

Further Readings –

• Güney, Yasemin Đ., (2007) Type and typology in architectural discourse

• Jong , T.M. de; and Voordt, D.J.M. van der, (2002) Design Research and Typology

Hi, can you please contact me via my email address and I’ll see if I can help you. cgraves at kent.edu

Hey i am a student of architecture in 4th year and in this year we are working or our concepts that how we form a vision and connect our design to it. So my vision was forming a building in urban typology. I have been researching it from past a week but im not understanding that how these designers are bringing the form and calling it a typology. Maybe I’m not clear that how typology work in design. Can yiu please help me?

LikeLike